The Threat of Japanese Encephalitis in the Philippines

We

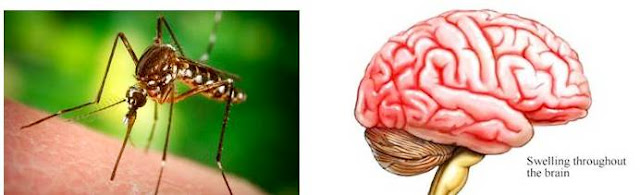

may not know it because it hasn’t been widely published but there is another

threat that comes from mosquito beside Dengue and its Japanese Encephalitis.

During the forum held last February 23 at the Dusit Thani, experts discussed

the burden of Japanese Encephalitis and we can fight it.

|

| Photo by Cherryl True |

Japanese

encephalitis (JE) is a leading cause of viral encephalitis in Asia. Transmitted by the mosquito vector

Culextritaeniorhynchus, the virus can cause inflammation of the brain, leading

to high fever, headache, fatigue, vomiting, confusion, and in severe cases,

seizures, spastic paralysis, and coma. It

could also mimic a stroke, as was the case reported in Davao during the second

half of 2016.

There

is no specific treatment for this disease.

JE is fatal in 20to 30% of cases and among those who survive, 30 to 50%

suffer from permanent disabilities.

Reports

from the World Health Organization (WHO) have estimated that there are

currently 3 billion people at risk for JE, living in JE-prone areas, including

24 countries in the Southeast Asia and Western Pacific regions. JE usually

occurs in rural and agricultural areas, however, an epidemiologic study conducted

by Dr. Anna Lena Lopez of the National Institute of Health (NIH) published in

2015, showed that the virus circulates in all regions of the Philippines, including

urban areas like Metro Manila, constituting a significant public health burden.

The

study showed that although majority of cases occur in children younger than 15

years of age, adults remain at risk, with 15% of cases occurring in individuals

older than 18 years. In tropical areas,

disease can occur year-round. Data from the Department of Health (DOH) Epidemiology

Bureau surveillance system revealed that for 2016, among 875 acute

meningitis-encephalitis suspected cases reported as of August 2016, 119 (14%)

were laboratory-confirmed for JE.

As

part of the government’s strategy to reduce mosquito-borne diseases, the 4S

program was implemented several years back. 4S stands for: Search and destroy

mosquito breeding places, use Self-protection measures, Seek early consultation

for fever lasting more than 2 days, and Say yes to fogging when there is an

impending outbreak. However,

mosquito-borne diseases are still on the rise.

According

to the WHO, the most effective way of reducing disease burden is vaccination

against the illness.6The THAT cites that there is clear evidence demonstrating

the impact JE vaccination has on disease burden in a population. Hence, the WHO

has recommended that JE vaccination be integrated into national immunization

schedules in all areas where JE is recognized as a public health problem.

The

WHO Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety (GACVS) has reviewed data on

the different types of JE vaccines (inactivated and live attenuated vaccines)

and has found them to have acceptable safety profiles. Local scientific bodies,

including the Philippine Pediatric Society (PPS) and Pediatric Infectious

Disease Society of the Philippines (PIDSP), have recommended that JE

vaccination be given as a single primary dose for those 9 months old and

above. For individuals less than 18

years of age, this should be followed by a booster dose 1 to 2 years after. Other preventive strategies for disease

control include bed nets, repellents, long-sleeved clothes, coils, vaporizers and mosquito control measures.

The

JE-chimeric vaccine, a live attenuated recombinant

vaccine, was first licensed in the Philippines in 2013. The vaccine is produced by Vero cell culture,

a cell culture technology recommended by WHO.It is the only JE vaccine

available locally and is approved for use for individuals 9 months old and

above, withhigh immunogenecity rates.

0 comments